- Aleph

- Anna Gat

- Ariel LeBeau

- Austin Robey

- David Blumenstein

- David Ehrlichman

- David Kerr

- Devon Moore

- Dexter Tortoriello

- Drew Coffman

- Drew Millard

- Eileen Isagon Skyers

- FWB Staff

- Gaby Goldberg

- Greg Bresnitz

- Greta Rainbow

- Ian Rogers

- Jessica Klein

- Jose Fernandez da Ponte

- Jose Mejia

- Kelani Nichole

- Kelsie Nabben

- Kevin Munger

- Khalila Douze

- Kinjal Shah

- Kyla Scanlon

- LUKSO

- Lindsay Howard

- Maelstrom

- Marc Moglen

- Marvin Lin

- Mary Carreon

- Matt Newberg

- Mike Pearl

- Mike Sunda (PUSH)

- Moyosore Briggs

- Nicole Froio

- Original Works

- Ruby Justice Thelot

- Ryne Saxe

- Simon Hudson

- Steph Alinsug

- The Blockchain Socialist

- Willa Köerner

- Yana Sosnovskaya

- Yancey Strickler

- iz

Thu Jan 13 2022

In 2014, a year before Ethereum launched, Trebor Scholz, a scholar-activist and professor at the New School in New York, coined a new term: “platform cooperativism.” In a blog post, Scholz outlined a bold alternative to the extractive Web 2.0 sharing economy: platforms that operated as cooperatives, collectively owned and controlled by their workers and users. The goal was to find ways to usher in a future where ride-sharing apps would be owned by drivers, grocery delivery platforms would be owned by personal shoppers, and sites like Patreon would be owned by creators.

Since 2014, platform cooperativism has become a growing global subculture in tech. At conferences in New York, Hong Kong, and Berlin, scrappy community organizers and social entrepreneurs come together every year to support each other, to exchange stories, to commiserate about the difficulties of finding funding.

Several years ago, I founded a digital cooperative called Ampled, an artist and worker-owned Patreon alternative for musicians. More recently, I have also participated in several DAOs, including Forefront, Seed Club, and Friends With Benefits. Having one foot in the platform cooperativism movement and another in the DAO space has been illuminating, and I have come to believe that both spheres are giving rise to valuable new tools when it comes to human organization, collective ownership, and cultural production. While it can sometimes seem like these innovations are happening in parallel isolation, I believe that there is a lot that these two communities can learn from each other — even opening the door to meaningful hybrid approaches between the two.

Cooperatives, or “co-ops,” are businesses where ownership is shared by workers, customers, or both — and operate on a one-member, one-vote basis. Although this ownership structure forms the basis of the cooperative model, its applications and cultures are varied. There are agricultural co-ops, just as there are digital cooperative tech platforms. This writing will primarily focus on worker and platform co-ops, but other examples include:

Co-ops:

- Consumer cooperatives

- Purchasing cooperatives

- Multi-stakeholder cooperatives

- Housing cooperatives

- Marketing cooperatives

- Producer cooperatives

DAOs, token-coordinated internet-native organizations that use blockchain as their foundation, take a variety of forms as well. These include:

DAOs:

- Protocol/platform DAOs

- Creator DAOs

- Service DAOs

- Curation DAOs

- Investment DAOs

- Social DAOs

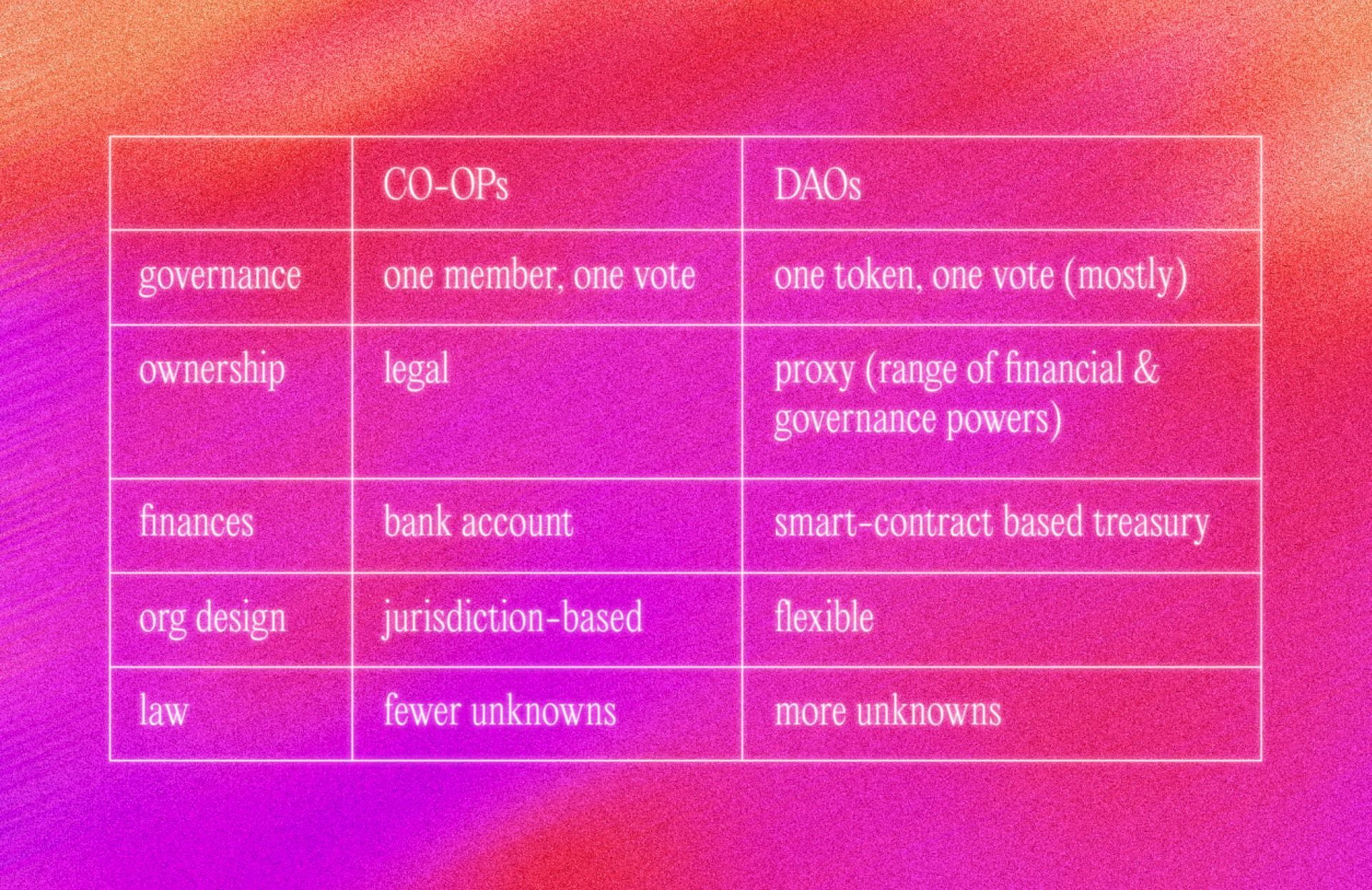

Although co-ops and DAOS are both collectively owned and co-determined organizational forms, there are some key differences. Primarily, cooperatives have one-member, one-vote governance. This means that people vote, not dollars. No single member of a cooperative can purchase more power than anyone else.

While it is possible for DAOs to emulate cooperative governance, it’s more common to observe the easier-to-implement governance pattern of one-token, one-vote, since verifying one’s personhood is still a nascent field in the world of blockchain.

Differences aside, there is a growing overlap in the idea spaces that DAOs and platform co-ops inhabit. Both forms seek to expand collective ownership and governance of digital infrastructure. Both have a culture that prioritizes collective control and the creation of shared goods.

From my experiences in the two spaces, I have noticed that DAOs tend to be better at enabling collective ownership at scale, even if their cultural understanding of the rights, responsibilities, and accountability associated with ownership is comparatively underdeveloped. And while cooperatives tend to be less successful in securing funding, they are also more likely, through their sober rejection of capitalist realism, to correctly address the root causes of inequity. Below, I’ll share some of the key takeaways I have gleaned about what DAOs and co-ops can learn from each other.

Ampled contributors, 2021

What DAOs can learn from co-ops

Historical Context

People in the DAO space would be mistaken to believe that collective modes of work and organization are a tech-related invention. In reality, communities have been practicing mutual aid and democratic ownership in nearly every corner of the world throughout history.

In America, the cooperative tradition has an overlooked history of marginalized groups that were forced to create solidarity networks for survival and self-sufficiency. In her book, Collective Courage: A History of African American Cooperative Economic Thought and Practice, Jessica Gordon-Nembhard, a professor at John Jay College, outlines examples of economic coordination that free and enslaved African-Americans engaged in hundreds of years ago, including pooling money to buy individuals their freedom and forming intentional communities and mutual aid societies. The Underground Railroad was itself a solidarity network. These forms of cooperation pre-date the Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers, a British consumer cooperative formed in 1844 to expand access to quality food and provisions among skilled workers forced out of work by mechanization, widely cited as the basis of the modern co-op movement.

During the Great Depression, Americans carved out alternative networks of barter and value exchange, such as The Unemployed Exchange Association of Oakland. Because existing power companies deemed certain areas too unprofitable to serve, much of rural America was powered by electrical cooperatives. The U.S. also has a rich history of community and local currencies, including Ithaca Hours and BerkShares.

DAOs have plenty to learn from these historical examples, especially when it comes to non-hierarchical work modes and collective decision-making. It can also be instructive to study failed co-ops, for mistakes to avoid. I’d argue, however, that there are three areas where examining cooperatives and solidarity networks from the past can be particularly instructive for DAOs: rallying people together around the fight for racial and economic justice, fostering a robust sense of shared ownership, and building communities on a foundation of shared principles.

Economic & Racial Justice

Co-ops often emerge as an attempt to respond to market failures and exploitative economic systems. They are designed to bring benefits to their members: good jobs, dignity, and collective agency. Because co-ops are motivated by serving members’ needs, rather than profit, they are often guided by racial and economic justice missions. There aren’t any particular structural mechanisms that advantage cooperatives to more effectively focus on social justice than DAOs; it’s more a question of founding motivations.

By contrast, in the crypto space, some of the most famous examples of collective economic organization have formed for the memes, or as exercises in commodification and speculation. Examples like PleasrDAO fractionalizing the Doge meme, or ConstitutionDAO raising upwards of $40 million to buy a copy of the U.S. Constitution, have value in that they suggest templates for new models of global economic coordination. So far, however, these DAO-ified money swarms rarely seem to coalesce around goals that involve helping underserved individuals and communities meet their basic needs.

There are some encouraging conversations happening around Decentralized Impact Organizations, which could become a useful framework for allocating resources towards longer-term social impact outcomes. And while there are a growing number of mutual aid and mission-driven DAOs (including the Free Ross DAO by PleaserDAO), these projects haven’t generated the same amount of collective excitement, support, or resources. For people who want to use Web3 to make a difference, though, the stories of co-ops like Cooperation Jackson and 40 Acre Co-op have plenty of wisdom to offer when it comes to banding together to pursue a common goal, and building an organization that reflects those values.

Ambitious Definitions of Ownership

Crypto networks and DAOs often use the concept of the “ownership economy,” an idea first articulated by venture capitalist Jesse Walden, as a kind of guiding philosophical infrastructure.

“The ownership economy doesn’t always mean a literal distribution of tokens, stock options, or equity,” Walden wrote in a post outlining the idea. “Rather, it means that ownership — which may manifest in the form of novel economic rewards, platform governance, or new forms of social capital — can be a new keystone of user experiences, with plenty of design space to explore.”

By defining ownership so broadly, this argument risks diluting the concept of ownership to mean little more than “exposure to upside,” or a “feeling of ownership.” As Cory Rosen, director for the National Center for Employee Ownership, has said, “A sense of ownership is like a sense of dinner.” But the “ownership economy” concept ignores some of the critical tenets of true ownership, like giving members transparency into investments and agreements, a voice in hiring and other important decisions, and the ability to hold leadership accountable.

This is where cooperatives have a long track record of expertise and a time-tested toolbox for creating robust shared ownership through legally defensible means: bylaws, operating agreements, and IP ownership, in addition to clearly defined rights, responsibilities, and lines of accountability.

As DAOs continue to develop novel forms of collective governance, it is useful to look towards smaller or older cooperative models as inspiration, from the bylaws of the East Bay Permanent Real Estate Cooperative, to Stocksy’s proposal flowchart, to Ampled’s decision-making matrix.

Shared Principles

There’s another thing cooperatives have in common: They tend to unite around a shared set of principles. The Rochdale Principles are a set of cooperative ideals developed by the Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers. Nearly two centuries later, cooperatives around the world still use them as a foundation.

The first three principles outline how cooperatives should function:

- Voluntary open membership

- Democratic member control

- Member economic participation

The other four principles outline shared virtues and values:

- Autonomy and independence

- Education, training, and information

- Cooperation among cooperatives

- Concern for community

Not all DAOs will be interested in adopting a shared set of principles. But for those of us who are motivated by cooperation, impact, and joining forces around a common social or technological goal, it’s important to ask ourselves the right questions: What will our shared values be? Do we want to prioritize transparency, participation, and collaboration, just as the open-source movement does? What we may find, if we do enough soul-searching, is that we share many principles with the co-op movement, including principle 6: that DAOs should seek to collaborate with other DAOs.

As new entrants rush into the Web3 ecosystem to form DAOs, it may be useful to develop a common set of principles that can guide us as we build Web3 — values that help us to avoid recreating the dark patterns of Web2, and that could perhaps form the basis of collaboration between likeminded DAOs. The DWeb Principles, a set of values that stress humanity and distributed benefits over “autonomous organizations,” are a good inspiration, although not comprehensive when applied to an organization of workers. Fusing the DWeb Principles with the Rochdale Principles could be a good starting point.

What Co-ops Can Learn From DAOs

Rapid Experimentation

In April 2021, Mirror founder Denis Nazarov took to Twitter to propose an idea for a tool called PartyBid that would enable groups of people to bid on and purchase NFTs. Shortly thereafter, PartyDAO came together, raised $100k, then quickly built and shipped an impressive product that allows for collective bidding and fractionalized ownership. In the span of a few short months, this distributed team created a collectively owned platform that has since facilitated millions of dollars of bids.

Since DAOs are blockchain-based organizations that usually are not tied to a corporate entity, they leave a lot of room for rapid experimentation in organization and incentive design. Members can collectively source an idea, funnel collectively managed resources toward shared goals, iterate, and ship with rapid speed.

Cooperatives, by contrast, often spend a lot of time hand-wringing with lawyers over bylaws and the process of incorporation, making them considerably more difficult to set up than a traditional company. Instead of being slowed down by the complex process of formalizing a traditional co-op, it may be instructive to examine DAOs like PartyDAO, which have the ability to quickly ship products and scale impact — providing an initial proof-of-concept to build on as an organization.

Image showing the Helium network

Bootstrapping Networks With Tokens

Cooperatives have long suffered from a capital conundrum. Because they are inherently for-profit organizations, eligibility for grants can be difficult. And because they revolve around group ownership and democratic collective control, they are functionally disqualified from accepting traditional equity-based VC investment, which requires selling large portions of ownership to investors.

In addition to being powerful tools for coordination and voting, tokens can allow cooperatives to more easily bootstrap when low on cash. Helium, a distributed network for “LongFi” wireless internet infrastructure, offers one example. To power the network, people across the globe set up routers in their homes and offices as nodes in the network. Nodes are compensated with $HNT, a native Helium token that represents governance power and holds value. Without this token, and clever economic incentives, it’s hard to conceive how a decentralized network on this scale could take shape.

Members of a tokenized community can also earn something tangible for their contributions. Tokens can be coded to automatically receive patronage dividends when there is revenue flow. This gives cooperative members or contributors the ability to capture the value they create, not unlike in time banking systems used by offline solidarity networks.

New Ways to Exit to Community

If a cooperative is maintaining a public or shared good, distributing tokens to early adopters of that good can be thought of as a kind of loyalty reward: granting people automatic membership, voting power, or ownership within a project, based on past consumption or support.

One example is the recent token airdrop by Ethereum Name Service (ENS), a public utility that allows you to register a Web3 username ending in “.eth” that is associated with your Ethereum address. This makes it easier for people to send and receive Ethereum without having to memorize long public keys.

ENS, which had been in development for over 4 years, was initially controlled by a small set of people. But they wanted to decentralize control and management to their community, so they assessed the users who had previously registered .eth domains and came up with an algorithm to fairly distribute 25 percent of the ENS supply to these users. After the initial distribution, the users ended up having more control and power than the core contributors, who collectively received 18.96 percent of the token supply.

While cooperatives will likely want to stick with one-person, one-vote models for decision-making, token airdrops can be a way of distributing rewards within loose and large networks and attracting more decision-making members to an organization.

For those who have been advocating for Exit to Community, or pathways for startups to transition ownership to their employees and stakeholders as an alternative to IPOs or acquisitions, DAO airdrops can be a powerful tool for distributing community control.

New Blended Models

Not surprisingly, there are a number of organizations currently experimenting with merging the concept of a DAO with the cooperative model. DisCo (Distributed Cooperative) is a framework that uses feminist economics to reorient our ideas of how DAOs can operate more like traditional cooperatives. Some other examples:

- ETHDenver, a conference and legal cooperative that recently launched a token

- Opolis, a digital employment cooperative that launched a DAO and its own $WORK token

- Common Lands, a “decentralized autonomous housing cooperative” aiming to help one million families become first-time homeowners through community-owned, affordable, cooperative housing

- SongADAO, a DAO formed around musician Jonathan Mann’s daily song releases, which recently incorporated as a legal cooperative

At the end of the day, the best framework for an organization may not be a choice between a cooperative or DAO model, but a blend of both. Incorporating cooperative values into crypto networks could take the form of a traditional cooperative that bootstraps its network through on-chain tokenized contributions. Alternatively, a DAO could decide to adopt cooperative one-vote governance in some instances.

By learning what we can from the past, and looking forward to the future, we can create communities that embody the best of both worlds: effective, principled, well-resourced organizations working to build a more equitable, democratic, and collectively-owned future.

Thank you to Stellar Magnet for generously co-authoring this piece and contributing valuable additional reporting and research. Also, thank you to The Blockchain Socialist and Scott Moore for feedback during the development of this essay.

Austin Robey is a founding member of Metalabel, Ampled, Unnamed Fund, and Dinner DAO. He also teaches Music and Platform Cooperativism at The New School in New York City.

Graphics by SIDNĒ and Fiona Carty.