- Aleph

- Anna Gat

- Ariel LeBeau

- Austin Robey

- David Blumenstein

- David Ehrlichman

- David Kerr

- Devon Moore

- Dexter Tortoriello

- Drew Coffman

- Drew Millard

- Eileen Isagon Skyers

- FWB Staff

- Gaby Goldberg

- Greg Bresnitz

- Greta Rainbow

- Ian Rogers

- Jessica Klein

- Jose Fernandez da Ponte

- Jose Mejia

- Kelani Nichole

- Kelsie Nabben

- Kevin Munger

- Khalila Douze

- Kinjal Shah

- Kyla Scanlon

- LUKSO

- Lindsay Howard

- Maelstrom

- Marc Moglen

- Marvin Lin

- Mary Carreon

- Matt Newberg

- Mike Pearl

- Mike Sunda (PUSH)

- Moyosore Briggs

- Nicole Froio

- Original Works

- Ruby Justice Thelot

- Ryne Saxe

- Simon Hudson

- Steph Alinsug

- The Blockchain Socialist

- Willa Köerner

- Yana Sosnovskaya

- Yancey Strickler

- iz

Wed Oct 12 2022

In 2013, I opened a gallery in Brooklyn called TRANSFER, dedicated to computer-based studio practices. The idea for TRANSFER stemmed from my recognition of an emerging avant-garde that was creating artwork on the internet, which I became interested in during my early years curating with a collective in Philadelphia called Little Berlin. Not long before, in 2012, Claire Bishop had published a seminal article in Artforum called “The Digital Divide” that asked why the mainstream art world seemed to be ignoring this new generation of artists right at the moment when digital technology was becoming inescapable in our lives. It seemed to me that these artists were onto something important, and it felt imperative to open a space that supported and elevated these emerging practices.

While working a day job in the tech industry, I developed a hybrid practice that moved between the principles of UX design (“great design is invisible”) and the studio setting, where artists were challenging technologies of power and exposing their underlying assumptions and systemic failures. The very same affordances that were seen as markers of success at my day job showed up in studio visits as conversations about hegemonic power, homogeneous identity, climate catastrophe, surveillance, and extraction. The cold, anti-humanist, capitalist tendencies of the tech industry became a site ripe for inquiry and reconsideration, offering a different understanding of how we, as humans, exist within a computational society.

As TRANSFER got off the ground, I found that the artists I was most compelled to work with were exploring the emergence of networked culture and online public space, experimenting with new economies and means of distribution, creating worlds within worlds, and reconfiguring technology’s intended outcomes. They were championing a new kind of art — one that centered transparency, openness, fluidity, malleability, and interaction. More often than not, this meant making work that critiqued the techno-utopian narratives of the tech industry while also defying the status-quo, scarcity-based contemporary art world and the principles and ideas it holds dear.

Working at this intersection, one quickly realizes that there is an inherent contradiction between the incentives of art and those of the “big daddy mainframe.” Industry’s goal is to use technology to shape the world and make money. The artist’s goal is to change our perspectives on the world, often by misusing technology. The studio produces subversive, non-utilitarian outcomes that question and challenge technologies of power. Artists have prescient visions of the near future; their explorations and experiments drive culture forward.

From the dawn of digital technologies to the hype-driven digital art world of the present, the history of art and technology tells the same story over and over again. Artists are often faced with a choice: Carry on making subversive work with little financial return, submit to the pressures of market forces, or act as R&D for a corporation. More often than not, we see art working in the service of industry. But what if it were the other way around? What if we lived in a world where industry felt a responsibility to support artistic exploration — where the productive forces of technology and the subversive forces of art worked together in the interest of mutual transformation?

I’m not the first to ask these questions: Back in 1967, the artists Robert Rauschenberg and Robert Whitman, together with Bell Labs engineers Billy Kluver and Fred Waldhauer, founded a collective called Experiments in Art and Technology. E.A.T. was born from the idea that art and industry could learn a lot from each other — that artists could tap into new insights about how technologies were poised to transform modern life, and engineers could gain a better understanding of how their inventions would impact society. There was a utopian ideal behind the endeavor: the collective believed this kind of interdisciplinary collaboration could lead to positive social change.

E.A.T. piloted these ideas with a pioneering event series called 9 Evenings: Theater and Engineering, which brought together ten artists and more than 40 engineers and scientists from industrial research and development company Bell Labs to develop new performances, immersive experiences, and interactive installations over nine months. The project culminated in nine evenings of performance at the 69th Regiment Armory in Manhattan, which attracted more than 10,000 visitors and set the course for a generation of artists working at the forefront of new technologies.

9 Evenings was special because it boldly positioned engineers in support of artists. There were dancers, musicians, and visual artists leading the programming, with a whole team of engineers working behind the scenes to bring their visions to life. One seminal work of art that emerged from this collaborative environment was Rauschenberg’s Open Score, a performance that was responsive to the characteristics of the exhibition venue itself and was a precursor to the immersive kinds of exhibitions we can experience today. Another was John Cage’s Variation VII, an exploration of randomness in which he allowed sounds that were “in the air at the moment of performance” to shape the composition — a concept that Cage would continue to explore during his rise to fame in the late ’60s as part of E.A.T.

The experiments born out of 9 Evenings were highly influential, as they helped give rise to a decades-long history of institutions focused on incubating and funding work at the intersection of art and technology. Two NYC-based organizations that formed adjacent to E.A.T. in the years after 9 Evenings are The Kitchen and Electronic Arts Intermix, which originated as spaces where “Television Generation” artists could explore the promises presented by new forms of broadcast and variable media. In the late ’70s and ’80s, annual festivals such as Ars-Electronica and ISEA became important sites of creation and academic exchange, leading to the expansion and proliferation of experimental media departments in colleges and universities. Focused on helping young artists develop new practices and an understanding of the digital avant-garde’s history and critical theory, these programs include SAIC FVNMA, UCLA DMA, Carnegie Mellon’s Studio for Creative Inquiry, NYU ITP, and MIT Media Lab. The online organization Rhizome was founded as an email list in 1996, and later, more organizations focused on experimental time-based media art — such as H3K, Eyebeam, and Gray Area — cropped up to support this underserved community of artists.

Over the years, these industry-adjacent organizations have played a critical role in incubating historically significant artistic scenes, while creating safe spaces for avant-garde artistic practice. However, despite this flurry of activity on the fringes of the art world, E.A.T.’s founding vision of a more symbiotic relationship between art and industry was a blip on the timeline. Starting with the emergence of programs like Art and Technology at LACMA in the ’70s, which fostered partnerships between artists and a host of California-based companies, a trend took hold in which artists became R&D for industry. They were brought into the site of business, asked to demonstrate the capabilities of new technologies, and paid to advertise and create “content” for corporations. This trajectory compounded in the 2000s with the mass public adoption of the internet, a medium that had the potential to be a new kind of public space for non-commercial creation on a global stage. Inevitably, this promising new frontier quickly gave way to centralization, with Web 2.0 and Silicon Valley companies culture-washing their stark capitalistic practices by commissioning artists as a business investment.

Over the last two years, we’ve seen an acceleration at the intersection of art and technology, due in large part to the new marketplace for digital art created by crypto. With the emergence of Web3 and NFTs, a market suddenly appeared for the longstanding community of artists making and publishing art online. Some happily adapted to this purported techno-utopian moment and managed to ride the wave by turning their art into tradable, blockchain-bound commodities. Others rejected the culture of Web3 and continued with their focused work in the studio, thoughtfully navigating the complex terrains of corporate interest, technology development, and the crisis of contemporary art funding in the aftermath of a pandemic.

Regardless of an artist’s relationship to Web3 technologies, decentralized economies are destined to have huge ramifications for the future of the digital avant-garde, as well as for art and culture more generally. As the NFT hype cools and the conversation becomes more nuanced, we’re experiencing the birth of entirely new ways of thinking about and articulating value. Web3 technology shows great potential for addressing a number of the problems that digital artists have been dealing with for decades, with tools for authenticating provenance, facilitating collective stewardship and governance, decentralizing storage, and sharing and distributing value.

At the same time, the relationship between art and capital feels more toxic than ever. “NFT time” — or the breakneck pace at which NFT markets churn, as is necessitated by the speculative market mechanics — is an unhealthy way of creating and producing. Many of the same hierarchies that we claim to be separating ourselves from (gatekeepers, hyper-financialization, and the centralization of power that we saw in the traditional art world) are already running rampant. Unfortunately, in our desire to do things differently, we have severed ties with the past and the values that matter most. These include understanding art as a way to make sense of the current moment, and valuing it for more than the revenue and “gains” it might generate.

Meaningful art takes time to develop through critique, thought, exhibition, and conversation. There is no way to take complex ideas “to the moon,” and the WAGMI culture that drove the emergence of NFTs as a new asset class is struggling to find meaning on the other side of the hype. It’s easy to see the dystopia we could be heading into if we allow “crypto culture” to assert its values over art and artists — which is why it’s important not to underestimate the challenges that lie ahead, and to do our part to flip the script on the industry-leading-art status quo.

If we want to live in a world that supports meaningful and subversive work (which I hope we do!), we need to step up and take responsibility for shaping the cultural legacy of our generation. In a new role, I’m working to develop E.A.T__WORKS, a Web3 organization focused on creating more expansive models for support and collaboration between art and industry, and for elevating the importance of participation in shaping culture. The organization takes its name from the very same E.A.T. that was behind 9 Evenings, aiming to reflect on that history and learn from its points of failure.

In building the mission and strategy of E.A.T__WORKS, I’ve had the opportunity to collaborate with original members of E.A.T., including Julie Martin, the director of the organization since its inception, along with members of the next generation of cultural stewards. Together, we’ve begun to zero in on a few strategies, or “patches,” that we believe can help mend the relationship between art and industry and take us into the future.

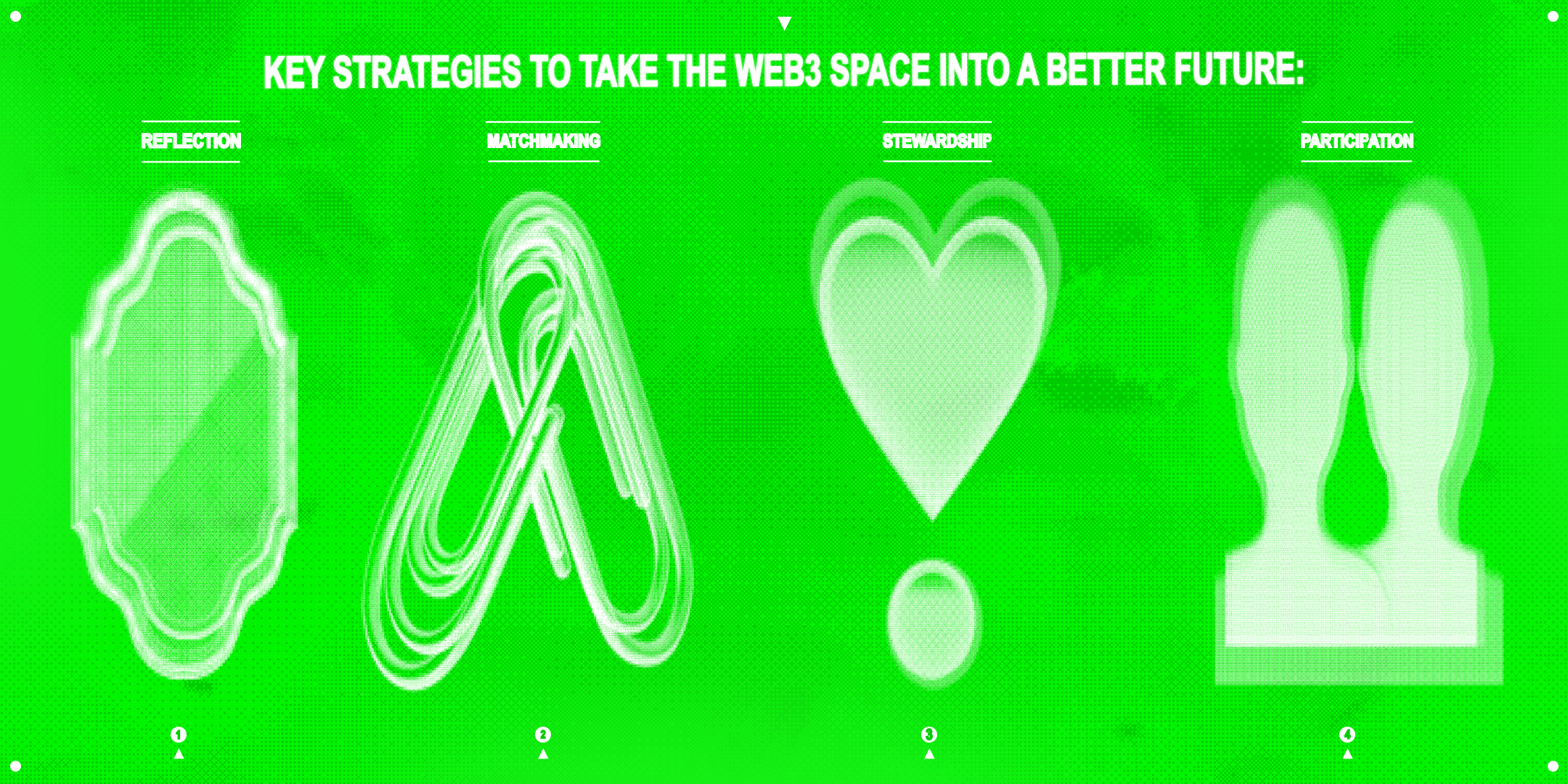

In a recent talk I gave at FWB FEST in Idyllwild, CA, I spoke about the four strategies that we need to lead with right now. We encourage anyone building in the culture-adjacent Web3 space today to consider them as they lay the groundwork for the future.

1) Reflection

How can we deepen our relationship with the present by looking into the past? There is a long history of artists making and distributing work in decentralized ways, and an equally long history of organizations doing work to support the digital avant-garde. NFTs are in no way the beginning of the story, and it’s crucial that we dig into the past to better understand where we’re going.

For anyone engaging with culture in the Web3 space, think about ways you can reflect on, and invest in, the learnings of those who came before you. Technocrats of the Imagination, by John Beck and Ryan Bishop, is a text that provides insight into this early moment of history — and if you don’t know which historical art and tech organizations are in your backyard, that is also a great place to start.

2) Matchmaking

One of the most innovative aspects of E.A.T. was how it matched participating artists with engineers who helped them realize their visions, using a system of computational “punchcards.” The key to collaborative creation is strong interpersonal relationships, an insight brought to the forefront in our conversions with MoMA Curator Michelle Kuo and E.A.T. Director Julie Martin.

At E.A.T__WORKS, one of our core areas of focus is iterating on this idea of matchmaking. How can we facilitate collaborative relationships between those who create culture and those who design the future? When the pressure of corporate ROI is stripped away, along with the uneven hierarchies and extractive frameworks of art world funding, what are the real needs artists have in the studio, and where do gaps in support still exist?

3) Stewardship

It’s time to invest in art as something that drives culture forward, rather than simply participating in this moment with an eye towards financial investment. Think about the many ways we indulge in luxury commodities, travel, and entertainment. What do we get out of those investments? What do we want our cultural legacy to be?

Stewardship is about slowing down, thinking about the implications of the moment we’re in right now, and investing our time, energy, and capital in ways that reflect our values rather than our financial prerogatives. By imagining how we want this moment in time to be remembered, we can reprioritize where to place our attention and leave the space better than we found it.

4) Participation

As we’re learning with Web3, distributed operational models are predicated on the idea of participating to build value together. With an upcoming series of Salons at E.A.T_WORKS, we are exploring a non-financialized model of participation focused on making space and time, sharing ideas, and connecting individuals and groups across disciplines. Simultaneously, we hope to create new behaviors around NFT collecting, and to prototype a decentralized stewardship model that can aim to preserve a wider representation of artworks from being lost in this moment of digital upheaval. By creating a space of mutual exchange, we hope to form a cooperative of like-minded stewards and participants who feel a sense of duty to actively invest in and shape the cultural legacy of our generation.

The history of art shows us that cultural value is not built overnight. By offering care and stewardship, seeking mutual understanding through art and ideas, and prioritizing the needs of artists, we prioritize our own humanity — ahead of profit, and ahead of power. If you’re reading this, you are likely engaged in these new digital paradigms. So, I’d like to end with an invitation: Make time to actively support subversive acts of creation.

Kelani Nichole is a technologist and founder of TRANSFER, an experimental media art gallery exhibiting decentralized networks and virtual worlds in contemporary art since 2013. Currently, she is building a new cultural organization as Head of Experience at E.A.T__WORKS.

Thank you to my collaborators Julia Kaganskiy and Regina Harsanyi for your support and brilliant insights in developing these ideas, thank you to Julie Martin and the E.A.T__WORKS team for your vision, and thank you to the women at FWB who see value in these ideas: Kaitlyn Davies for prompting the talk at FWB Fest, and Emilie Friedlander and Willa Koerner for helping give shape to this story.

FWB Members are invited to attend E.A.T__WORKS’s upcoming Salon Program from October 21 – 29 in NYC at Betaworks, which includes experimental performances, an interactive salon dinner, a conversation on collecting and stewardship, and artist talks and screenings.

Images by Carlos Sanchez